Liberty Tree Foundation

Foundation for the Democratic Revolution

Beyond Insurgency to Radical Social Change: The New Situation

Beyond Insurgency to Radical Social Change

The New Situation

John Foran

The Arab Spring and U.S. Occupy movements surprised the world in 2011, showing that movements for radical social change remain viable responses to the intertwined crises of globalization: economic precarity, political disenchantment, rampant inequality, and the long-term fuse of potentially catastrophic climate change. These movements possess political cultural affinities of emotion, and historical memory, and share oppositional and creative discourses with each other and with a chain of movements that have gathered renewed momentum and relevance as neoliberal globalization runs up against the consequences of its own rapaciousness.

Three paths to radical social change have emerged that differ from the hierarchical revolutionary movements of the twentieth century: 1) the electoral path to power pursued by the Latin American Pink Tide nations of Ecuador, Bolivia, and Venezuela, 2) the route of re-making power at the local level as in Chiapas or seeking change at the global level as does the climate justice movement, both of which bypass the traditional goal of taking state power, and 3) the occupation of public space to force out tyrants, as in Tunisia and Egypt.

This paper assesses the strengths and limitations of each path, arguing that social movements and progressive parties together may possess the best chances for making radical social change in this new situation. These threads of resistance may also point toward a future of radical social change as we imagine their enduring results, self-evident and more subtle.

Political Cultures of Opposition as the Threads of Creation

Cover photo: Susan Meiselas.

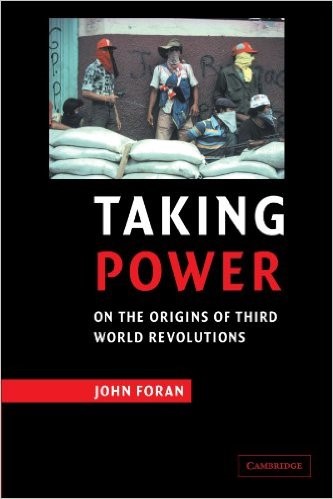

In my 2005 book Taking Power: On the Origins of Revolutions in the Third World I proposed a hypothesis about the origins of revolutions that brought together the economic and social dislocations of dependent capitalist development, the political vulnerabilities of dictatorships (and, paradoxically, of truly open polities where the left could come to power through elections), and a conjunctural economic downturn accompanied by a favorable moment in the world system where leading outside powers did not (or could not) intervene. Looking at the world since 2009, we see versions of each of these: the glaring contradictions of neo-liberal capitalist globalization, the persistence of personalist regimes (especially in the Arab world, and now, in 2017, in the United States) and wide disenchantment at the hollowing out of representative democracies in Europe, North America, and Latin America, the deepest and most dangerous global economic downturn since the 1930s, and finally, the attenuation of U.S. power due to the military occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, growing public debt, the rise of Asian economic centers, and the financial bubbles that brought on the great recession.

In the twentieth century, when all of these more or less structural conditions presented themselves, the final, requisite piece for fundamental social change was one of agency and culture: the ability of revolutionaries and ordinary citizens to fashion powerful political cultures of opposition capable of bringing diverse social groups to the side of a movement for deep social change, as happened in the Mexican, Russian, Chinese, Cuban, Nicaraguan, and Iranian revolutions. It should be noted that there are also political cultures of legitimation that states draw on, and that these can fray for many reasons, so that in a Gramscian sense there are always multiple political cultures on both sides of a particular state/civil society divide, whose proponents constantly maneuver for position, and ultimately for hegemony….

In the twenty-first century, the nature of movements for what we might now call radical social change rather than revolution has itself changed, as activists, reformers, dreamers, and revolutionaries globally have pursued nonviolent paths to a better world, intending to live and act as they would like that world to be. That is, the ends of justice are no longer held to justify the means of violence, but the means of non-violent resistance reflect and guarantee the ends that they seek. In this, they embody and illustrate the virtues of “prefigurative politics” and in particular, horizontalist ways to realize them.

I have recently begun to call these positive, alternative visions “political cultures of creation.” Movements become even stronger when to a widely felt culture of opposition and resistance they add a positive vision of a better world, an alternative to strive for to improve on or replace what exists. In this sense, some of the differences between old and new movements for radical social change seem to include the attempt to get away from the hierarchical organizations that made the great revolutions and move in the direction of more horizontal, deeply democratic relations among participants; the expressive power of using popular idioms more than ideological discourses; the growing use of nonviolence; and the salience of political cultures of creation alongside political cultures of opposition and resistance….

More than 100,000 march in the streets of Copenhagen, December 2009 under the banner of System Change Not Climate Change. Source: Climate Justice Action Network.

Problems and Prospects

The obvious political question is: Can these new political cultures of opposition produce – or at least contribute to – some type of global transformation of the sort that is needed to deal with a world in crisis? These cases have shown their ability to move beyond ideology in favor of the strengths of popular idioms demanding social justice and have shown us some of the advantages of horizontal networks over vertical hierarchies. But how to fashion large-scale popular spaces for democracy, and how to articulate the discourses that will bring together the broadest coalitions ever seen onto a global stage constitute great challenges….

What, then, lies between or beyond direct action and elections? One idea is to combine electing “progressive” governments and forging social movements to push them from below and beside to make good on their promises, and to make links with other movements, nations, and organizations everywhere. In other words, rather than the dichotomous choice between seeking to change the world through elections versus building a new society from the bottom up, the future of radical social change may well lie at the many possible intersections of deeply democratic social movements and equally diverse and committed new parties and political coalitions….

Conclusions

It will take time for these open-ended revolutions to blossom and reach their full potential. Important to this process will be the articulation of powerful political cultures based on participatory (not formal, representative, elite-controlled) democracy and on economic alternatives that challenge the neo-liberal capitalist globalization that created the conditions for their flowering in the first place – namely, we will need to nurture powerful and attractive political cultures of creation as well as opposition.

The people in each of these places – the most radical ones, the younger ones, the most savvy – reject the dysfunctional social and political systems they have inherited. They are not about renegotiating anybody’s ruling bargain. And they are succeeding. Or at least they haven’t failed. And, like their counterparts everywhere, they are not done yet.

System Change Not Climate Change Marcher, New York City, September 2014. Source: Journal of Wild Culture.

*****

A very special announcement

And – you heard it first and you heard it here – I am considering – both seriously and with a healthy dose of whimsy – running for president of the United States in 2020…

My proposal is that we beat Trumpism and the poisonous, fatally compromised neoliberalism of the Democratic Party with a new plan: the creation of a new kind of party-like organization that comes out of and exists alongside all of the new movements for radical social change – Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, the Sandernistas, the Dreamers, the climate justice movement, and so many others. That we bring a slate of candidates from these movements and from organizations such as the Green Party and the Socialist Alternative and the Working Families and independents everywhere in 2020 (and in 2018 if we can), that is younger, more diverse, more working-class than anything ever seen before in the US – because it will be a convergence of many forces, not led by any of them, or by any individual and certainly not under some all-encompassing grand ideology, but rather united by a set of shared values – deeply democratic, cooperative and egalitarian, in tune with the rhythms of the earth, and committed to the provision of free education, health care, shelter, social security, and meaningful work, where no one is left out, let alone behind.

That’s a long sentence – but you get the idea.

This basic program is easily paid for by deep cuts to the military budget and steep increases in taxes on the wealthy and on corporations.

This is a movement that as yet has no name. But it has a future. If such a thing could be accomplished, I would be honored to stand for president (let’s have a little sense of humor about all this, and some fun too while we’re at it) in the election of 2020. I am open to working alongside anyone who wants to go in this direction, which is the only way through the crisis – crises – that now plague us. We must do so quickly, because the inexorable warming of the planet is poised to condemn us all if we don’t rise up NOW and act in the name of humanity, with our sisters and brothers all over the globe, in the greatest, grandest intersectional, intergenerational, international wave of like-minded people ever seen, powered by compassion, community, and communication.

I’d be pleased to hear from anyone for whom this resonates deeply. Let’s resolve to do this, for ourselves, our families, our communities, our shared existence with all living creatures everywhere, and for the future of all – in fact a future much better than the present – because if we can dream it, so might we build it, together.

All thoughts and suggestions on what would be this ultimate test of scholar-activism, simultaneously and experiment and a real revolutionary process – in all its ridiculous immodesty – are most welcome!

Is the world ready for this?

Teaser photo image: The clown brigade at the Global Day of Protest, Warsaw, Poland, COP 19 UN Climate Summit, November 2013. Photo by John Foran.

(Forward)

Earth News: More than News of the World

Beginning of the Year Special edition

January 11, 2017

As we approach the end of this series, I am left wondering what I myself can say that would offer hope and value to the discussions to come in this new year.

I am a sociologist who studies movements for radical social change. For twenty-five years I devoted myself to learning what I could about the great revolutions of the twentieth century, and especially what it was that brought them about. I thought that doing so would be of use to people who wanted to see a better world come about in our lifetimes.

And I did learn a lot, and was especially drawn to trying to understand what compelled “ordinary” people to do extraordinary things in the name of something better. This focused my attention on the importance of culture, emotions, the siren song of ideologies and the power of more popular, accessible ways of articulating grievances and a vision, and on how people found ways to come together and turn these deep, existential sources of action into the effective practice of changing their world.

As the first decade of the twenty-first century unfolded, I felt a need to do more than study and understand the world, and I turned from doing what might be called “radical scholarship” to something altogether different that is sometimes confused with it: scholar-activism (see my 2010 manifesto on this). Scholar-activism is not my favorite term, as it implicitly elevates scholars and activists above others, but it is a useful coupling that suggests that what we think we know about radical social change and how to bring it about means nothing if we don’t actually put it to some useful purpose (for scholars, this is an “experiment,” while for activists it means actual social change). And in doing so, we are quickly humbled by the limits of what we know and the fruitfulness of what others, being and acting together, can know and do.

And as the global justice movement against neoliberal corporate capitalism scored victories in places like Seattle, only to be derailed by George Bush’s war in Iraq into repurposing itself to deal with the terrible consequences of that war, and then was followed by a new radicalism in the Occupy movements and Arab Spring of 2011, a new upsurge of hopefulness about the possibilities for radical social transformation was placed back on the agenda and within reach of scholars frustrated by doing only analysis in academic settings that are both constrained by their own peculiar culture and hermetically sealed off from the movements themselves.

The ah-ha moment for me came when almost by chance and favorable circumstance I decided to go to Copenhagen in December 2009 and saw the global climate justice movement come of age against the backdrop of a miserably failed global climate negotiation by the world’s political and economic elites at the expense of both the planet and the people who live on it.

From then on I was hooked, and started travelling along a new path, doing whatever I could to support and be part of this movement. And Resilience – especially my amazing editor, Kristin Sponsler – has been kind enough to help me reach so many like-minded writers and readers and learn so much more about the prospects for surviving this crisis or at least fighting to maintain that possibility. I am immensely appreciative of this wonderful space.

So below I offer my own thoughts on how to move closer to the worlds we want, based on much comparative reflection on the stories of people everywhere who have acted in the name of radical social change, which for me, means something like “deep transformation of a society (or other entity such as a community, region, or the whole world) in the direction of greater economic equality and political participation, accomplished by the actions of a strong and diverse popular movement,” a definition loose enough to encompass both the great revolutions of the twentieth century and the new paths to radical social change of our own.

The piece that follows is a bit academic-y. I no longer write so much for an academic audience, but I have always striven to make my work as accessible as possible to any interested audience. The “big idea” here is that to make radical social change in the twenty-first century, we may need to rethink what a political party is and create an unbreakable bond between whatever new kind of party we come up with and the social movements that fuel it and make it possible.

For those who are never going to grapple with this essay in its entirety, I provide a summary and some key extracts below [above], and for those who wish, here is a link to the whole essay, which was published in Studies in Social Justice in 2014.

Grassroots Organizing